Looking to improve indoor air quality? you are not alone.

Since the beginning of 2020, indoor air quality has gone from a very niche topic to mainstream news and now perhaps to overload (I get the irony). There has also been a rush of new blood into a fledgling market with many people hoping to capitalise on prospective funding like that made in the USA, the so called “Covid Dollars”.

The reality was the UK government seemingly had its’ head in the sand regarding aerosol transmission. Perspex screens shot up everywhere making airflow worse and we sanitised everything in sight, massively raising levels of VOCs. Showing that you were doing something was more important than doing something shown to be effective.

As the UK is so driven by guidance and legislation, the majority of landlords and occupiers sat on their hands waiting from direction from on-high. A lack of forward guidance from government left the newly expanded IAQ improvement industry struggling to find direction for 18 months. Many companies formed to capitalise on the seemingly imminent opportunity presented by Covid have now folded. Many of these failed ventures fully invested in a single “novel” solution that has subsequently not been recommended by SAGE or CIBSE. You can see from the comments on social media that there are a lot of frustrated people whose independently verified solution is not the one supported by SAGE or CIBSE. Many a current sales strategy is now centred around discrediting other solutions rather than promoting the virtues of the solution the person is promoting. I guess we have the US to thank for this, as many of the novel clean air technologies are imported from there, along with their very un-British sales and marketing styles.

So where is the industry going? What solutions are going to be recommended and critically, funded.

A £25M Covid business fund released in Scotland in October prioritised ventilation improvements; offering the majority of funding for CO2 monitors, extract fans and re-instating existing ventilation openings, minimal funding was made available for portable air purifiers. £3.31M of Covid grants for schools in Wales will be allocated according to the results from 30,000 CO2 monitors provided over the autumn term. CO2 monitoring has also been made available to schools in England, 300,000 of these sensors were eventually provided, much criticism has been directed at the government saying not enough CO2 monitors have been made available, and about the amount of time it took to deliver them.

In England, schools had to wait a long time for guidance on what funding, if any would be made available. Portable air purifiers were evaluated by the DfE and a pair of small HEPA air purifier units by Dyson and Camfil were made available on a government portal. Schools were then told to purchase these from their own funds. So far, only a handful of schools had sufficient funds available to place orders through this portal. A £1.8M ongoing trial that began in September will see 30 schools in Bradford putting standalone HEPA air purifiers against upper room ultraviolet systems to see if either technology can make a meaningful difference to Covid infection rates. This trial was intended to run for 18 months, but the government has been under pressure to act much sooner, with the news that secondary school children will be asked to wear masks being deemed unacceptable. The decision was made just prior to Christmas that on top of the 1000 already made available for specialist settings, 7000 HEPA air purifiers would be funded by the government for classrooms where CO2 levels cannot be kept low enough for covid mitigation. In order to demonstrate that classrooms cannot be sufficiently ventilated, over an extended period, teachers will need to gather CO2 readings and submit to the DfE.

At the beginning of January, a poll of 2,000 teachers by the NASUWT union found that 56 per cent said they didn’t have a CO2 monitor for checking the air quality in their classroom. 34 per cent of those who had been provided with monitors reported that CO2 levels often or sometimes exceed levels at which the Government said action is needed to improve ventilation.

The government has chosen to deploy only HEPA purification over other “novel” technologies like UVC or bipolar ionisation. This mirrors guidance from CIBSE, that any solution other than ventilating or particle filtration should be deemed “novel” and unproven. There is a particular note in the procurement documentation that systems that emit ozone should not be included. Perhaps this note is linkedo the backlash against the Welsh government announcing over the summer that they would be providing 1800 ozone sterilisers for classrooms in Wales. This ozone solution was presumably conceived when the primary concern was about fomite transmission. Ozone, like bipolar ionisation is able to decontaminate both air and surfaces. It perhaps seemed like an appropriate solution at the time but thankfully the concerns about ozone safety meant the procurement was halted in October. The next challenge will be supplying these HEPA purifiers to schools in time. The supply-chain issues affecting the wider HVAC industry have not spared the purifier market, lead-times are long, and stock is sparse.

The long awaited update to Part F was released in December. There was no radical overhaul in terms of indoor air quality but there were a number of interesting points to note.

Sadly, as with many documents that take a long time to produce, the updated WHO figures for permissible NO2 levels were not included, so the document references 2010 figures as acceptable rather than the latest, lower 2021 numbers.

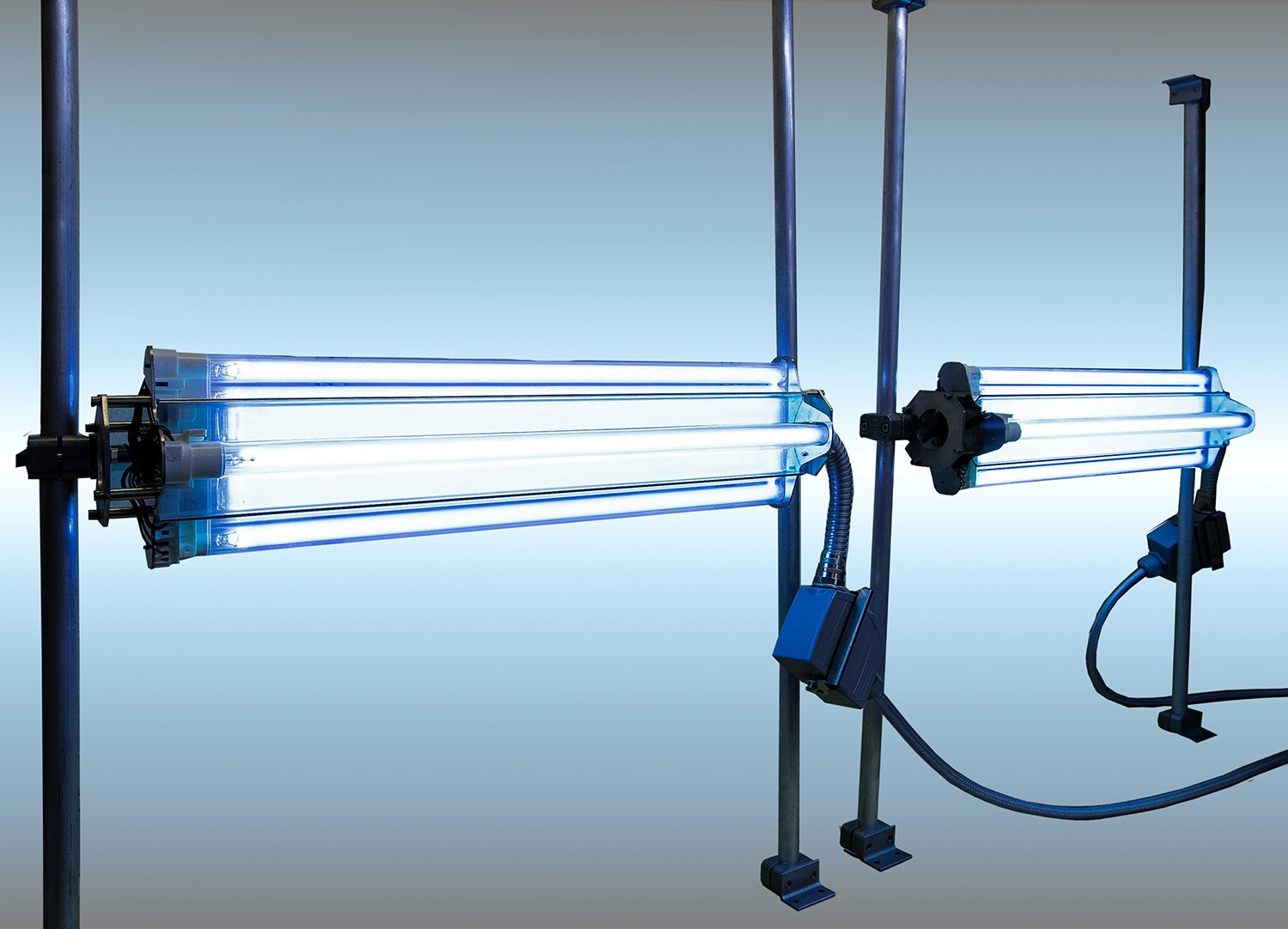

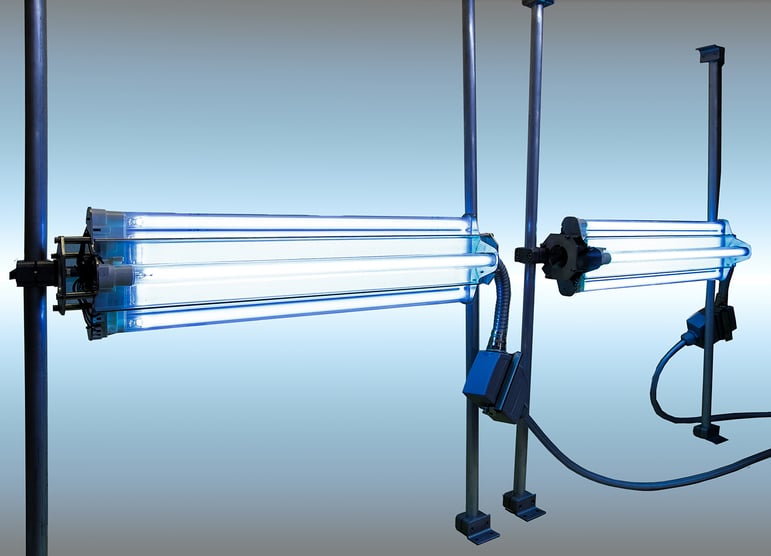

According to the newly updated Part F, for any office HVAC systems that re-circulate air between rooms, either HEPA or UV-C germicidal irradiation systems are required to mitigate the risk from re-circulated pathogens. The majority of UK spec office ventilation designs don’t deploy centralised recirculation, so this may not drive a significant change, but ever empowered tenants may start raising questions about the risk posed by existing ventilation systems.

ARM Environments UVC system

One of the new sections states that when external pollutants vary with the time of day, building operators should reduce the flow of external air or close ventilation intakes. This is potentially a great way of minimising maintenance on a building and reducing the ingress of pollution, but goes completely against current Covid mitigation advice. If the same was applied to minimising the intake of outdoor air during periods when the outside temperature is very high/very low, this presents a significant opportunity for carbon savings. This will require extensive indoor and outdoor air quality monitoring, something that the industry is ready to supply.

Lots of the latest guidance and recommended action centres around user operation of natural ventilation directed by air quality monitoring. This may work well in an environment where there is a defined person in charge, like a teacher in a school classroom. When it comes to other spaces, if operational experience of heating and cooling systems has taught us anything, it is that the person who complains the most gets to set the temperature within the space. This does not bode well for multi-occupant spaces relying on windows for providing sufficient ventilation.

Over the Christmas break I felt comfortable asking to have windows opened in friends and families houses but at a meeting to discuss infection control solutions at a South Coast hospital in December, I did not have the same level of confidence to go and open windows above people’s heads. This was in a staff area of the hospital canteen where up to 50 people rely on single sided ventilation from openable windows. Needless to say, the windows were not open and there was no ventilation provided to the space, a crazy situation when the NHS is under such intense staffing pressure.

Just a handful of UK companies were providing clean air solutions pre-pandemic, the newly formed ones that hope to survive will need to invest in ventilation systems training and settle down for the long-haul, there is not going to be a quick fix to the UKs’ chronically under ventilated building stock. After the immediate rush to supply portable air purifiers as a quick fix, the UK is likely to revert to improving ventilation rather than deploying “novel” solutions. If this is via natural or mechanical remains to be seen, hopefully the revised CIBSE AM10 natural ventilation guidance incorporates lessons learned from the pandemic, as traditional natural ventilation via windows has been proven to be ineffective at a time when ventilation is needed most.

This Article was Published in Modern Building Services' February 2022 Issue.